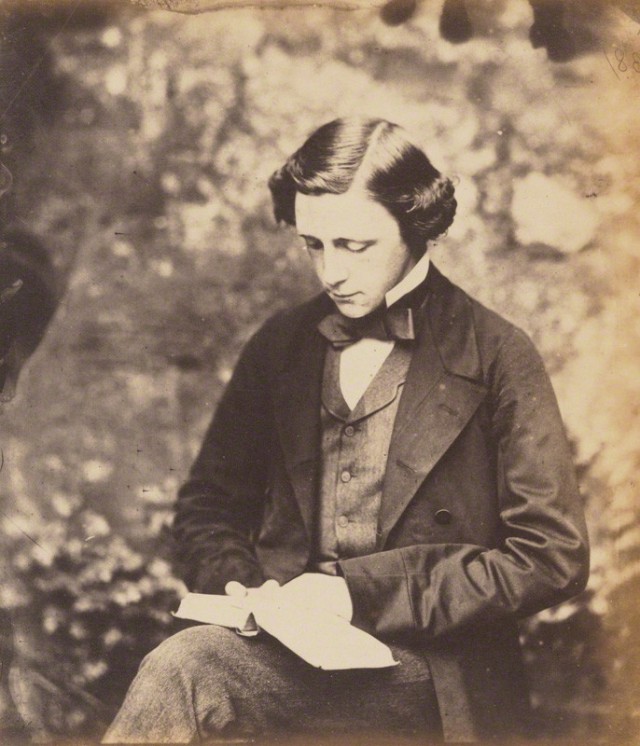

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll have been close to my heart since I first read them, when I was about 8 years old. Like many children before and since I was simultaneously fascinated and disturbed by their unpredictability, their frenetic madness and surreal logic — all enhanced by John Tenniel’s immortal illustrations (the image of Alice with the long neck, her eyes wide with surprise, was particularly startling). As I grew older I was keen to learn more about the books themselves, their Victorian social-historical context, as well as becoming interested in the life of the man himself, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. The eventual outcome was that I wrote my undergraduate dissertation on Carroll’s literary and artistic connections with the Pre-Raphaelites, exploring not only his writing (prose and poetry), but also his photography and illustrations — looking to assert Carroll as an accomplished visual artist, besides being a mathematician and children’s author.

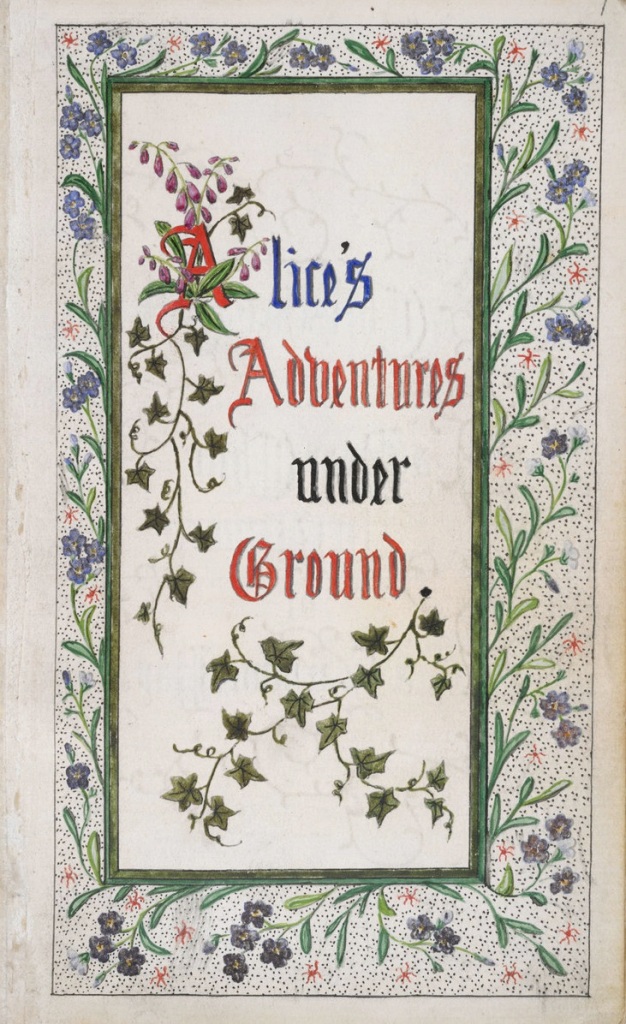

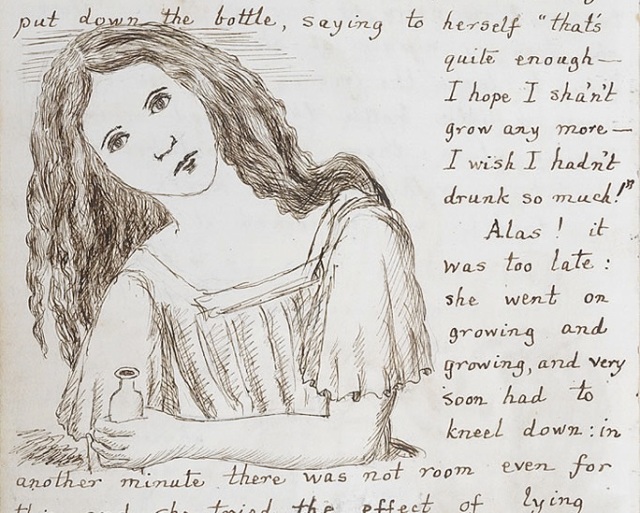

Carroll created this gorgeous title-page for the manuscript which would eventually become Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, then titled Alice’s Adventures under Ground. His inspiration clearly comes from medieval manuscripts, with its border of forget-me-nots, the widths different around each edge, and its delicate gothic lettering interlaced with foxgloves and trailing ivy. This is Carroll the book designer at work; the handwritten, illustrated pages, which took about two years to complete, were eventually bound in leather and gifted to Alice Liddell, the daughter of the Dean of Christ Church who is often inevitably labelled the ‘real’ Alice. It is interesting that William Morris, who attended Exeter College, Oxford from 1852-6, was also closely examining medieval manuscripts and practicing illumination and decoration (the earliest examples, illuminating poems and tales by Robert Browning, himself and the Brothers Grimm, date from 1856-7). Although they lived in Oxford at the same time, however, there is no mention in Carroll’s meticulous diaries that he ever met a Morris, or a Jones — although he did meet Arthur Hughes while the artist was staying in Oxford to assist with the Union murals.

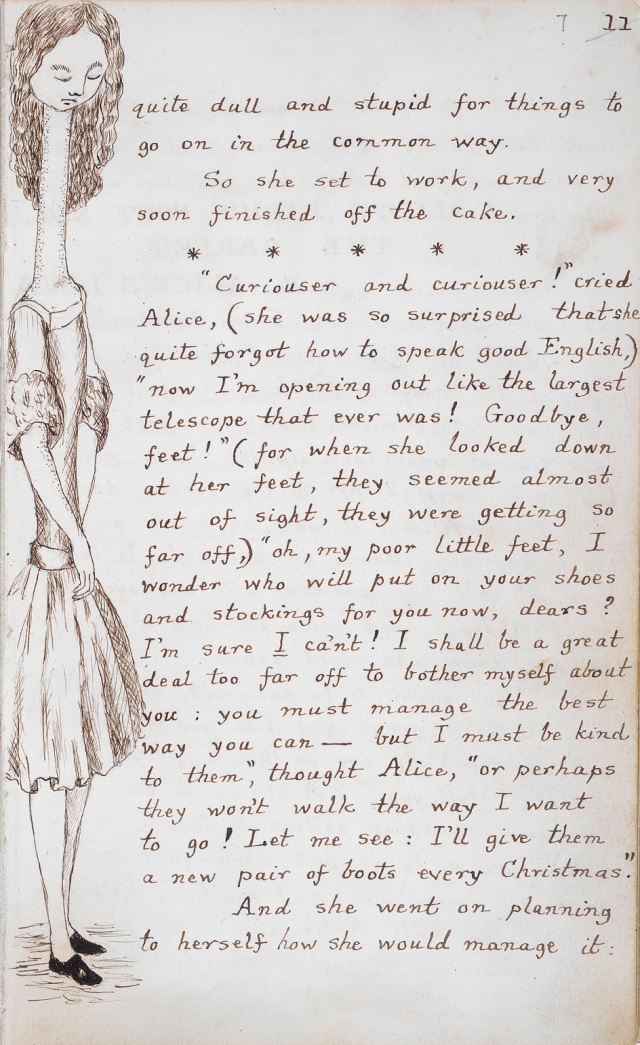

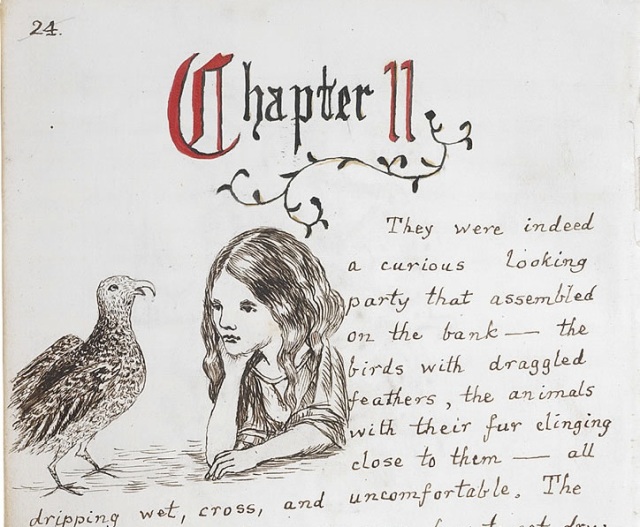

The Alice in these drawings is a melancholy Pre-Raphaelite girl, whose flowing hair and wide eyes bear little resemblance to Alice Liddell. Like Rossetti, Carroll lavishes particular attention to the waves of her hair — in fact in October 1863, when Carroll was midway through drafting these illustrations, he visited the Rossetti family at Chelsea to photograph not only their portraits, but also several drawings of women in D. G. Rossetti’s studio. Thus, the Alice of under Ground is the closest we can get to seeing Carroll’s own original vision of his heroine and the Wonderland she dreams up — like the drawings of William Blake and Samuel Palmer, we are afforded a glimpse into a private, personal world of fantasy.

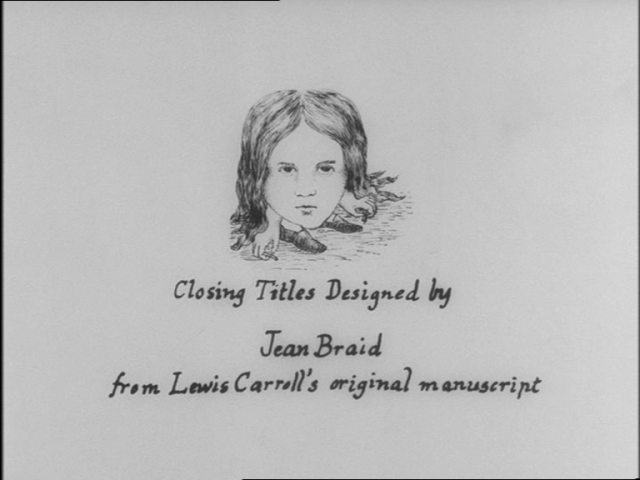

The melancholy, matter-of-fact oddness of Carroll’s illustrations fed into what is both the best Alice adaptation (in my view) and my all-time favourite film: the 1966 version, directed for the BBC by Jonathan Miller. This film, which I first watched in 2007, entranced me from the opening shot — Alice, tousle-haired and sullen, peers out from among vine leaves and recites the first lines of Wordsworth’s Immortality Ode in voiceover. This was an interpretation of Lewis Carroll unlike anything I had seen before, and it has stayed with me ever since. Gothic, brooding and deeply Victorian in design and tone, it intersperses its hazy summertime atmosphere with moments of Pythonesque silliness supplied by Peter Cook’s Hatter and Peter Sellers’s King of Hearts. I later learnt that the opening titles and end credits (seen above and below) were lovingly copied from Carroll’s under Ground manuscript.

Miller’s film conjures the vanished world of nineteenth-century Oxford through the lens of a dream — as dreamt by the daughter of a dean. Julia Trevelyan Oman, the set designer, opted for a High Victorian approach, cluttering the interiors with bric-a-brac and taxidermy. Dick Bush, the cinematographer, purposefully shot in crisp, silvery black-and-white to evoke the work of early photographers such as Roger Fenton, Julia Margaret Cameron and of course Carroll himself — also using wide-angle lenses to distort proportions during the growth and shrinking scenes.

All the scenes, with the exception of the final trial scene, were filmed on location at various country houses and estates in southern England, as well as at Sir John Soane’s Museum (for the Caterpillar, dusting architectural models). This approach, which differs significantly from the studio-based settings of most Alice films, creates a landscape of crumbling rectories, dusty churches, sculleries, meadows and walled gardens at the height of a Victorian summer.

At the centre is a young actress whose performance as Alice has divided opinion over the years. Anne-Marie Malik, age 13, the daughter of a barrister, wanders through Wonderland with a characteristic silence and solemnity, a kind of detached, bohemian moodiness. This is completely at odds with almost all other adaptations, which portray Alice as a neat, rather cutesy sort of girl. Indeed, Miller chose Malik out of many other hopefuls precisely because of her sullen, nonchalant, seen-and-not-heard attitude, which he felt fitted his chosen Victorian mood. True to this notion, many of Alice’s lines are delivered in voiceover, without her opening her mouth — the dialogue with the Cheshire Cat, for example, is conducted as an imaginary conversation in her head as she strolls through a dappled forest. She appears to have little time for the absurdities of the (animal mask-less) adults around her, gazing into the distance and delivering her words in deadpan fashion.

Her face is frequently framed with leaves and vines — this Alice is a child of nature, soon to mature into adulthood. Close-ups are reminiscent of Cameron portraits and Rossettian studies of the female face; there are so many arresting images and carefully composed tableaux that it is impossible to screenshot them all without essentially showing you the entire film. More than other Alice adaptations it achieves the authentically surreal atmosphere of a dream, but does so through simple feats of editing (cross-fading, for example), cinematography and sound.

Another memorable aspect of the production is its soundtrack, composed of natural sounds (cooing wood pigeons are especially recurrent) and a score by Ravi Shankar, the Indian sitarist who most famously worked with the Beatles on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released only months after Miller’s film was broadcast in December 1966. The clip below shows Shankar at work on recording passages for the film.

Miller has stated that he used sitar music to hark back to the British Empire in India, and also because the languid droning of the sitar echoes the buzzing of insects, the texture of dry grass, on a hot day. These intentions have been slightly lost on contemporary reviewers and bloggers, who tend to view the Shankar soundtrack as an attempt at ’60s psychedelica. Certainly it’s very much of its time, and sounds remarkably similar to ‘Within You, Without You’, the woozy, sitar-led song by George Harrison on Sgt. Pepper. Lewis Carroll, of course, appears among the cast of faces on Peter Blake’s album cover.

This has only been a short look at one of the more memorable and original Alice in Wonderland adaptations, a film whose details and subtleties repay multiple viewings. Thankfully it’s available on DVD, though in a slightly different release to the BFI disc from 2003 (which includes a highly informative commentary by Miller himself). Miller’s Alice, like the brilliant and equally distinctive 1988 film by Jan Švankmajer, remains something of a curio alongside the bigger, better-known versions by Disney, Hallmark and Tim Burton (not that Burton’s film was actually any good). However, anyone with an interest in Carroll and his Victorian milieu will, after seeking it out, certainly find the film a treat.