The British director Ken Russell’s documentary-style biopic of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the wider Pre-Raphaelite circle, titled Dante’s Inferno, has been beautifully restored and released on DVD/Blu-Ray in the UK, thanks to the BFI. The film – one of several documentaries on the lives of artists and composers that Russell made for the BBC throughout the 1960s – was produced for the BBC’s Omnibus series, and first aired on BBC2 in December 1967. It remains one of Russell’s early masterpieces, appearing only two years before Women in Love (1969) and four years before the notorious The Devils (1971), and one can see in it the genesis of the director’s favourite traits and themes: artistic excess, madness, hallucinations, desire/eroticism and performances which are occasionally (but deliberately) camp, over-the-top or amateurish. (All these are especially evident in Gothic, Russell’s bonkers 1986 interpretation of the Byron-Shelley gathering at the Villa Diodati which gave birth to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.) Moreover, Dante’s Inferno marks the Pre-Raphaelites’ first outing on the small screen; The Love School followed in 1975, Desperate Romantics in 2009. The screenplay, by Austin Frazer, undoubtedly drew much from William Gaunt’s influential biography The Pre-Raphaelite Tragedy (1942), a title Russell originally hoped to use for the film.

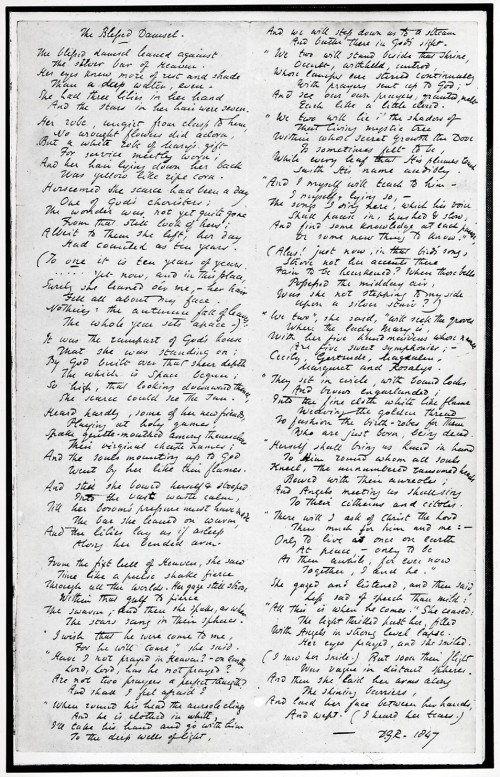

The film’s opening shot establishes a mood of gothic melodrama: a coffin is drawn out of its grave and prised open to reveal a woman’s rotting corpse, before a hand reaches in, draws back the burial shroud and extracts a mouldered book (later we will learn that the corpse is Elizabeth Siddall, while the book, containing all Rossetti’s poems, was placed there by Rossetti after her death). Given Russell’s interest in fantasy it is surprising that he opts for the grisly truth of Siddall’s exhumation, dispelling the popular myth that her body was found to be untouched by decay even after several years in the ground. This suits the realism of the documentary genre, but also suggests that we are about to witness, or even to confront a story which has been literally unearthed from the past.

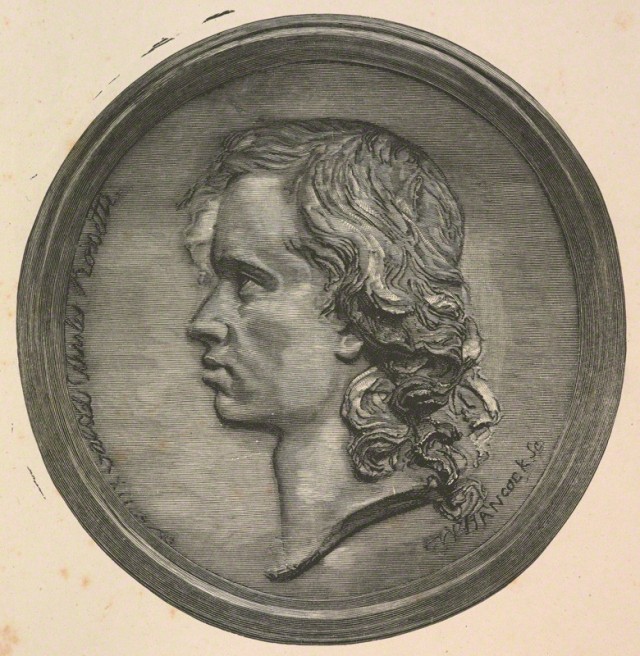

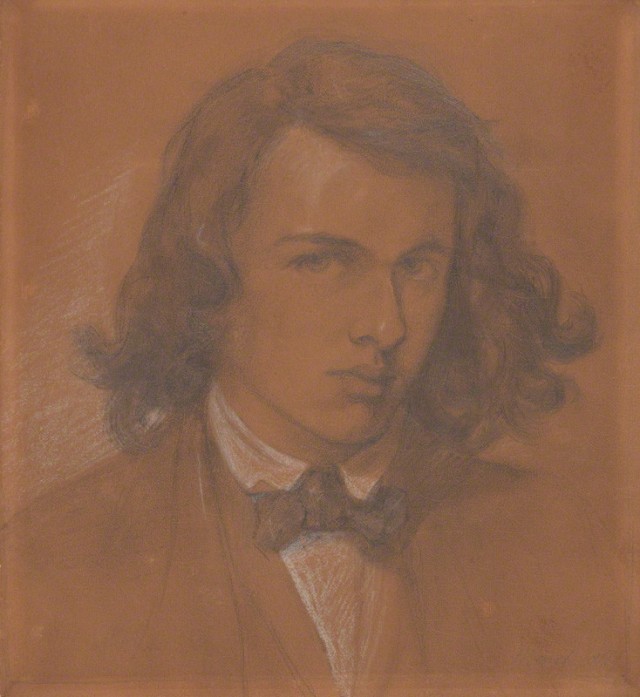

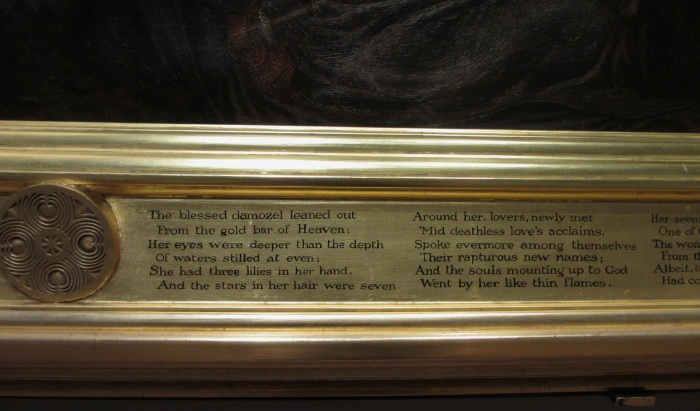

Immediately after this is a bonfire scene, intended to encapsulate the Brotherhood’s hatred of all things stale and Academic. ‘Down with the pretty ladies and Gainsboroughs!’ they cry, as they throw saccharine paintings by Reynolds and others onto the fire. The voiceover – another documentary technique – draws clear parallels with the spirit of Revolution happening in France when the PRB was founded in September 1849. Oliver Reed’s Rossetti (I should here note that Reed is more ruggedly handsome than Rossetti actually was) leaps through the flames and yells at the camera, before experiencing a vision of a medieval damozel in armour towering over the pyre – a shot which could be lifted straight out of a German silent film by Fritz Lang or F. W. Murnau, and which introduces Judith Paris as Elizabeth Siddall as a Joan of Arc figure. Of course it is highly unlikely that any such bonfire actually took place, but this is one of the many licences which Frazer’s script takes with the truth; history is stylised to explain the Brotherhood’s artistic motivations to the audience as succinctly as possible (the film is only 88 minutes long, so there’s a lot to fit into a short running-time).

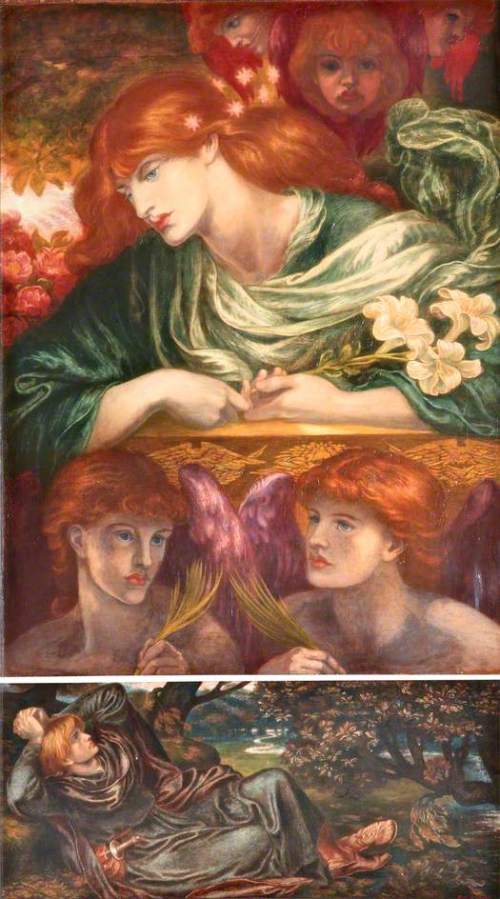

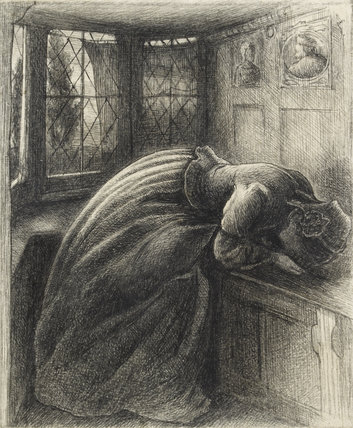

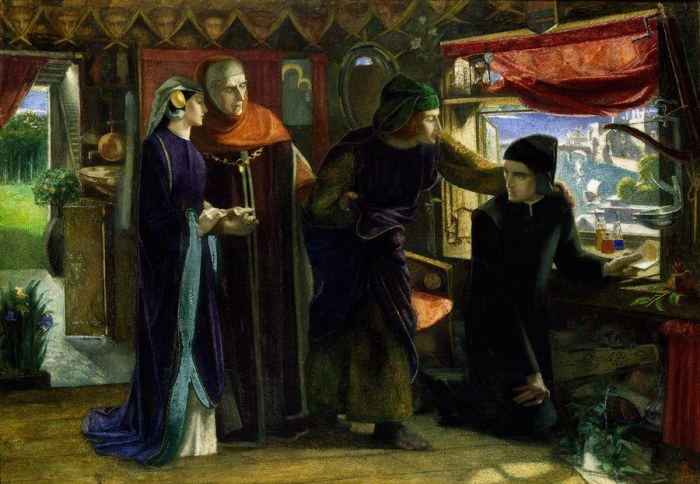

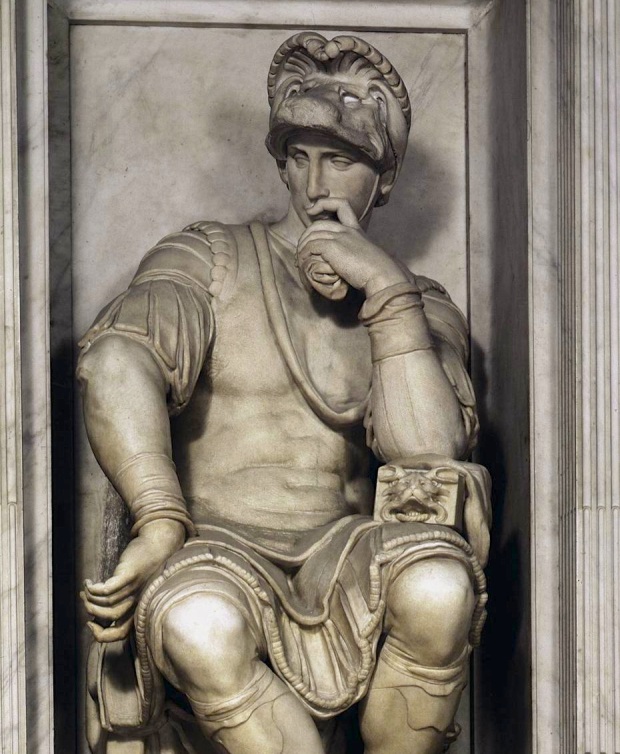

I shan’t now proceed to analyse the film scene by scene. Instead it’s best to present some stills and let the images speak for themselves (and also to show the beauty of the BFI’s restoration).

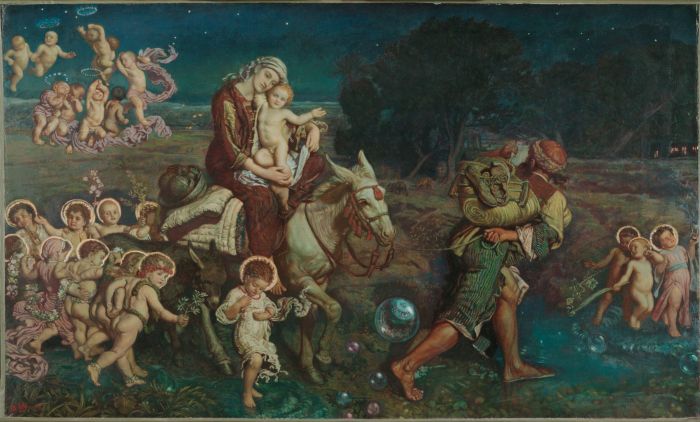

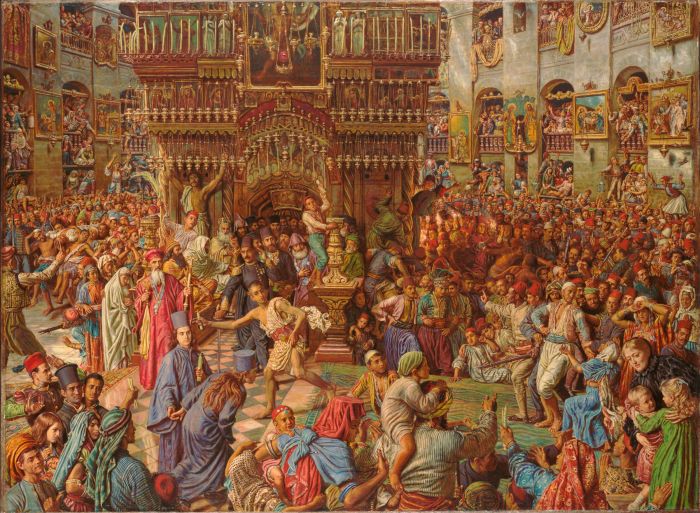

Dante’s Inferno does manage to include characters who were bafflingly absent from Desperate Romantics – Christina Rossetti for one, and her brother William Michael (though he hardly says a word). It also uses original, untampered reproductions of the many artworks, rather than the frankly dodgy reconstructions used in certain other shows (for which see Kirsty Walker’s interesting blog post). Real Pre-Raphaelite locations are also used, notably Red House:

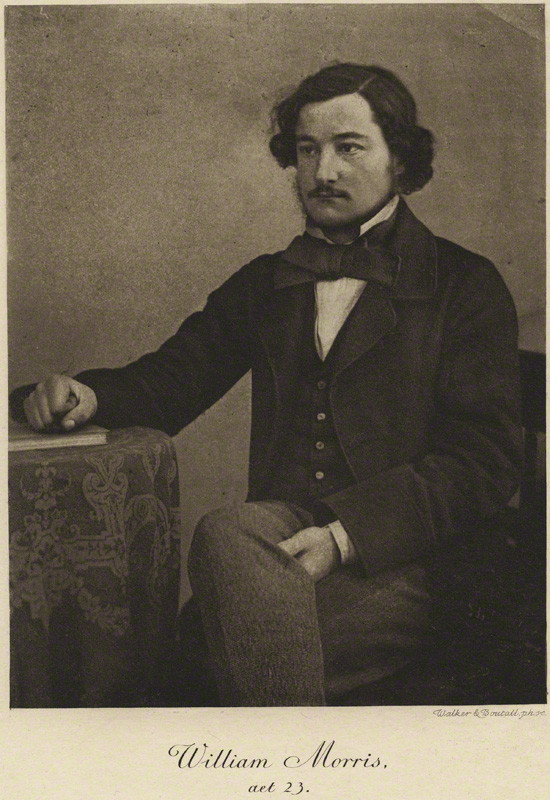

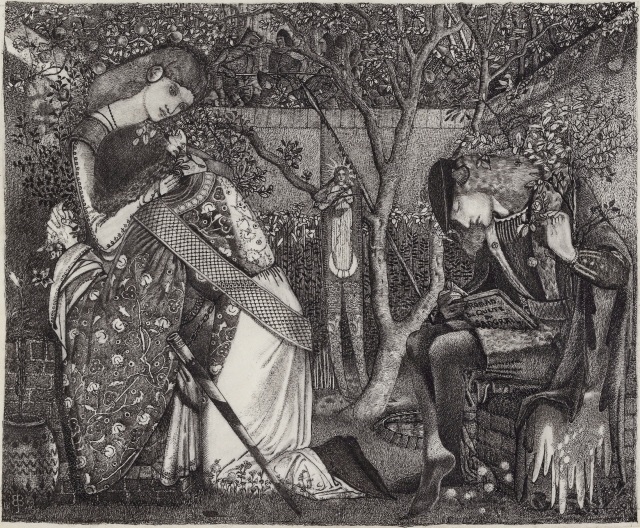

For me, one of the film’s real successes is its portrayal of William Morris. Despite the sheer number of historical characters jostling for attention on screen, Andrew Faulds’s performance stands out, capturing Morris’s dual qualities of boyish enthusiasm and romantic sensitivity: in one scene he cavorts around the garden of Red House pretending to be a chicken, while in another he softly recites his poem ‘Praise of My Lady’ to Jane Burden whilst punting down the river in Oxford. (This is another of the film’s interesting features, with many original Pre-Raphaelite poems by the two Rossettis, Morris and Swinburne read aloud either in voiceover or by the characters themselves.) It also helps that Faulds bears some resemblance to Morris.

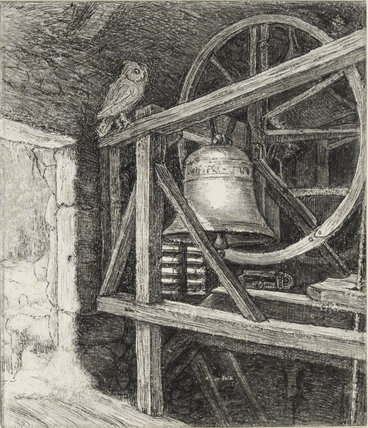

In the film’s second half, which introduces the ‘second wave’ of Pre-Raphaelite artists and models, there is a noticeable shift in tone from light, jovial antics to the brooding melancholy which was foreshadowed in the macabre opening sequence of the coffin. Velvety shadows and low lighting predominate, and at times the film has a quality of 1920s German Expressionism (Nosferatu, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari), the aforementioned Fritz Lang, or even films from the Czech New Wave such as Juraj Herz’s The Cremator (1969), with its wide-angle lenses and moody, black-and-white cinematography. These visual elements mirror the narrative itself, as Rossetti descends into madness and despair and declines in health following the death of Elizabeth Siddall and the presence of a new ‘muse’ in the form of Jane Burden (Gala Mitchell).

Russell was originally keen to film Dante’s Inferno in colour, as Brian Hoyle in the DVD booklet explains:

Russell passionately lobbied the BBC to allow him to shoot the film on colour stock. He scouted locations in Scotland and the Lake District, which he said contained colours he ‘didn’t think existed outside the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites’. He also wrote that the film ‘cried out for colour more than any subject I have yet come across’, and even went so far as to suggest how he could colour-coordinate the palate of the film to match the personalities and work of the four protagonists. Scenes with Rossetti and Millais would be ‘lush and over-ripe’, those with Holman Hunt would be bright, light-headed and hallucinatory, and those with Morris would be ‘ominous, dark, deep and brooding’. The BBC, however, had only recently begun investing in colour and due to the increased cost they were reluctant to take a risk on a feature-length project directed by someone as unpredictable as Russell.

Of course, the film is not perfect. Though centred on Rossetti, Austin Frazer’s screenplay does perhaps cram too much into its short running-time, with the result that some incidents feel rushed or jumbled. Characters such as Emma Brown (wife of Ford Madox) are suddenly introduced, only to vanish from the film a few scenes later, while Ford Madox himself is never shown; nor is it immediately clear to those unfamiliar with the Pre-Raphaelite history who exactly is being depicted. As a result, many of the characters – except for Rossetti, Siddall and Morris – feel one-dimensional, popping up in short, random cameos. This can be particularly problematic for the women in the film: for example Jane Burden, my favourite of the Pre-Raphaelite models, spends much of her time reclining or standing in the same mannered postures as John Robert Parsons’s famous photographs of her, speaking little, frowning often and never breaking out of her role as a kind of artist’s lay figure. Gala Mitchell, who plays Jane, was herself a professional fashion model, so any moody posing is done very well, and she certainly looks the part; her dark, heavy features are an appropriate contrast to the bright-eyed Siddall.

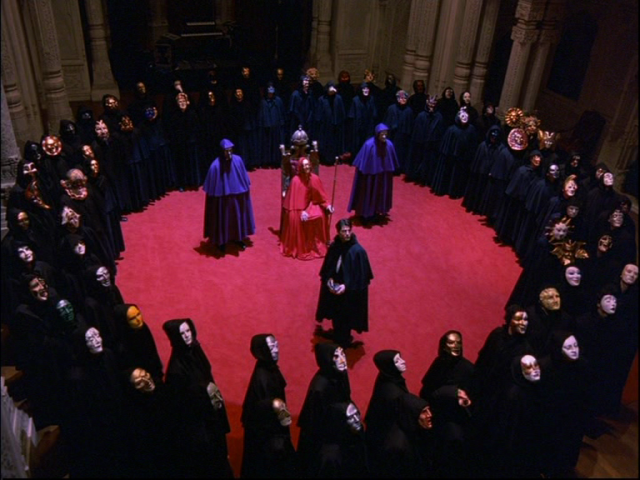

Some viewers may find the performances stilted, hammy, wooden or other words of that ilk, though this is down to Russell’s preference for using untrained actors. The director’s trademark moments of zaniness – see the scene where Algernon Charles Swinburne (played anarchically by the British poet Christopher Logue) prepares to ravage an automaton in a decadent gin house – could also be perceived as unnecessary or over-indulgent. Still, this doesn’t seem all that strange given that the personal histories of the Pre-Raphaelite men and women are often baffling in themselves, with their numerous affairs, obsessions, foibles, decadent lifestyles (exotic menageries included) and occasional bouts of grave-digging; these seem tailor-made for a Ken Russell film, in which, very often, anything goes.

Anyone with an interest in the Pre-Raphaelites should definitely watch Dante’s Inferno. Despite its flaws, inaccuracies and anachronisms the film evokes its Victorian milieu with a kind of carnivalesque joy, while its handheld documentary style does create a sense of intimacy with its audience – something that other, more measured BBC productions tend to lack. In focusing on Rossetti, whose life was the most classically tragic of the ‘big three’ Pre-Raphaelite Brothers, Russell ultimately addresses the failure of artists to live up to their own ideals of life and love. Muses waste away, friendships and relationships sour, mental and physical health deteriorate, painting and poetry are frustrated. Art is a struggle.